Sarah-Ann Echeverria

Professor Cacoilo

Art & Women

Due March 7th, 2017

The Evolution of Women in Art & Society

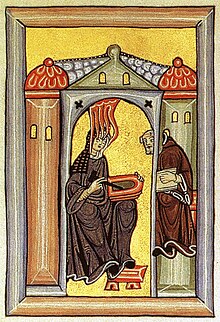

The Middle Ages can be recognized for its excessive use of religion, enforcement of gender roles, and patriarchy, among other qualities. As like much of history, the Middle Ages was a time of oppression for women. Their lives were predestined by the Christian social roles they were expected to fulfill. These roles included, "obedience and chastity, by the demands of maternal and domestic responsibility, and by the feudal system organized around the control of property.” (Chadwick, p. 44) Women during this time were condensed to the sexiest beliefs that because a woman bares children as a result of her biology, that is her occupation, and because a woman becomes a wife, she is property. Joining a convent was the only way women could break the social stigma. Convents were progressive during this era, allowing women to become educated, although they were forbidden from becoming educators, as another role for women in society was to satisfy the male gaze, seen but not heard. There are few known female artists from the Middle Ages. Art dated during the Middle Ages often were religiously motivated, and although many of the works were anonymous, it is assumed a portion of the artists were women who were given the opportunity to create pieces "...working in businesses owned by male family members, or living as nuns in convents." (Guerrilla Girls, p. 19) Arguably, the most noted female artists of this period was Hildegard Von Bingen, a maverick nun from Germany. Against fear of humiliation, Bingen spent a decade creating, Scivias, her first book. She details thirty-five visions, believed to be from God about corruption within the church, and encourages others to live a just life.

Hildegard Von Bingen, Scivias, 1142-1152

The Renaissance Era was a time of rapid progression and challenging the ideas that were previously in place. Although there continued to be restrictions on women, this period offered women more privileges. They were now allowed to divorce under certain circumstances, teach or attend a university in Bologna, and undergo an abortion. Some women were even encouraged by their families to pursue an art medium, which was rarely done in other time periods. Artemisia Gentileschi was one such women, who entered the art world through influence of her artist father. The Renaissance granted her a level of freedom in which she took advantage of and used to create vengeful, yet beautiful art works. As a teenager, she was raped by Agostino Tassi, a man with a tumultuous past that worked for her father. After refusing to marry her, which would have ruined her reputation, he was taken to court by Artemisia's father. Although he was found guilty and sent to prison for a year, Gentileschi achieved her revenge through paintings that encourage female empowerment and break the ideology that women are weak beings. Judith Slaying Holofernes is one of her most recognizable pieces. The biblical story is that of Judith, a young Jewish women, who murders an invading general by seducing him and cutting off his head; she is the heroine of her people. Gentileschi's version of the story is often analyzed and labeled as a feminist piece because "...many artists show[ing] Judith looking away as she cuts off Holofernes' head. They think a women could not bear to look while doing such a deed..." while Gentileschi shows "...Judith intent on accomplishing her mission, and unafraid to face carnage and death." (Guerrilla Girls, p. 37) She used her platform to, literally, paint women with a different lens then previously seen before.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, 1612

The 19th century was just the beginning of female artists establishing themselves without oppressing restrictions placed by men. Although communities of women artists, where there was a mutual support, began to arise, men in society continued to be a hurdle for the women. Men continued to hold arrogant, and sexist beliefs. The artists faced, “Critics [who] were quick to challenge the displays for their lack of ‘quality’ and women once again found themselves confronting universalizing definitions of ‘women’s’ production in a gender-segregated world” (Chadwick, p. 229) There was no solid proof of evidence that the women's pieces were significantly of lesser quality, it was simply because they were women that their works were assumed to be lesser to that of the male artists. Although the negative criticism followed them, women continued and progressed through the art world. Female artists, already considered controversial, explored impressionism, the equally controversial style of painting that occurred in the 19th century. It is known for its small, thin, visible brush strokes, lack of form, colors, and emphasis on an accurate depiction of light. The art of impressionism is meant to capture a moment and display it as a memory, rather than with photorealism. Berthe Morisot was one artist who explored this genre and painted everyday subjects. Psyche, is one art piece that depicts a young girl looking at her body in a mirror. It looks like a blurred image, a memory, but brings attention to an emphasis on body image, which affects women even in today's society. Women are told by society that have to look a certain way to please others, specifically men, because they are always to be looked at as a result of the male gaze.

Berthe Morisot, Psyche 1876

The history of female artists was not an easy one. Women faced many difficulties through the Middle Ages, into the Renaissance and during the 19th century. It is now the 21st century; sexism is alive and well. The struggles women, not only in art but in society as a whole, face continues to be on going battles. But as the history of women in art has shown us, women are progressive beings, who do not settle and bare the yoke society places on their gender. The fight for gender equality will live on through women who do what they love, against the protests of others.

Works Cited:

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. Londres: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.

The Guerrilla Girls' bedside companion to the history of Western art. London: Penguin, 1998. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment